English

The Wounaan language is not a formally taught language, unlike other indigenous languages in Panama like, for instance, the Guna language. The Guna language is currently taught in schools within Guna communities, with Panama’s Ministry of Education continuing to take actions cementing it as the first language taught to Guna children, with Spanish serving as a secondary language.

In speaking to Danitza, a member of the Wounaan community in Puerto Lara, Darien, I learned that there were efforts from local community members to implement the Wounaan language into curriculums, but that these efforts have thus far been unsuccessful. Danitza went on to explain that with each new generation, she feels that the language is being lost. She says, “I estimate 60% of the words used in conversation are in Spanish.”

In Panama, there are currently very few initiatives dedicated to the preservation of indigenous languages, with even fewer focused on woun meu. One notable effort is a children’s book written in woun meu in collaboration with Julia Velásquez Runk, Associate Professor of Anthropology at the University of Georgia and researcher at the STRI. The story is set within the Wounaan culture, and marks a significant part of the preservation of the Wounaan language.

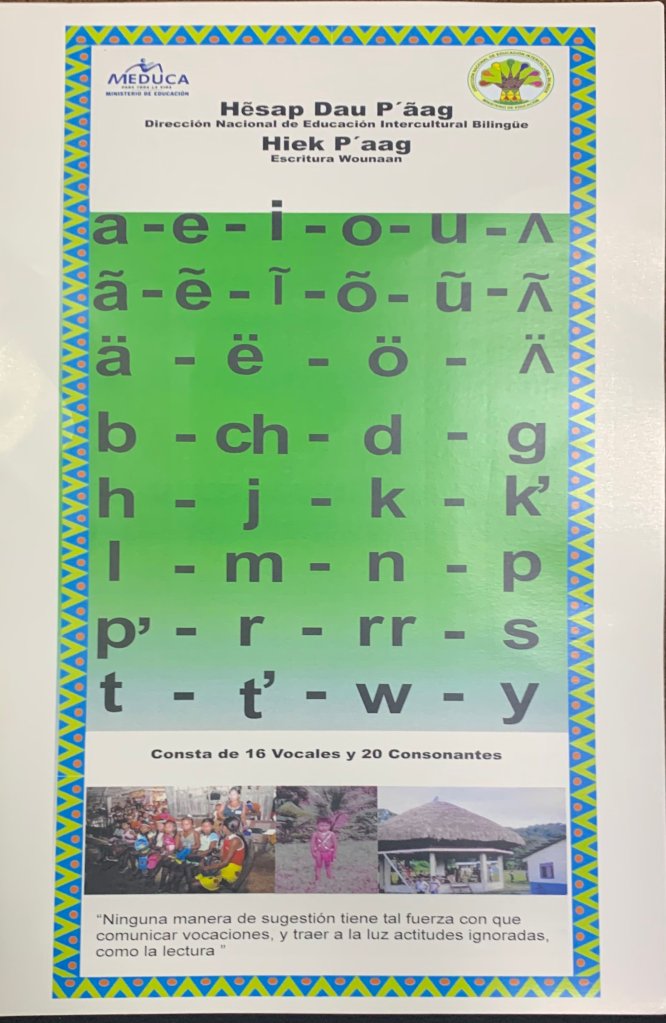

Most importantly, though, are the efforts revolving around Bilingual Intercultural Education and the Law 88 of 2010. The law officially recognizes the languages and alphabets of indigenous groups in Panamá. Previously, the Panamanian government had only recognized indigenous languages as dialects, thus preventing the formal teaching of these languages in schools. Community leaders from the different indigenous peoples of Panama came together to push for the law to be passed in the National Assembly.

Bilingual Intercultural Education is considered by Wounaan scholars to be the best way forward in preserving the Wounaan language for future generations. Yoni Cárdenas, leading Wounaan expert in Panama’s Ministry of Education, discussed at several panels in the 2023 Feria Internacional del Libro de Panama (themed around indigenous issues) the current struggles of pushing forward Bilingual Intercultural Education. He described the process of putting together an official Wounaan alphabet through working with leaders of different communities to create drafts that then must be approved by the National Assembly. This is why, he says, it has been so slow to actually get teaching materials to schools.

Preservation efforts for the Wounaan language are more important than ever today. Indigenous advocates in Panama are determined and hopeful to prevent the loss of their languages.

SPANISH

El idioma Wounaan no es formalmente enseñado como otros idiomas indígenas en Panamá, como el idioma Guna. Actualmente, el idioma Guna se enseña en las comunidades Guna, con el Ministerio de Educación de Panamá continuando a reforzarlo como el primer idioma enseñado a niños Guna — y el español de segunda lengua.

Hablando con Danitza, parte de la comunidad Wounaan en Puerto Lara, Darien, aprendí que había esfuerzos de miembros de la comunidad para implementar el idioma Wounaan a los planes de estudio, pero estos esfuerzos han fracasado. Danitza explico que con cada nueva generación, ella siente que el idioma se está perdiendo. Dice, “Estimo que el 60% de las palabras usadas en conversación son en español.”

En Panamá, hay pocas iniciativas dedicadas a la preservación de los idiomas indígenas, y aún menos dedicadas al woun meu. Un esfuerzo notorio es un libro infantil escrito en woun meu en colaboración con Julia Velázquez Runk, Profesora de Antropología en la Universidad de Georgia e investigadora en el STRI. El cuento se sitúa dentro de la cultural Wounaan y marca una parte significativa de la preservación del idioma Wounaan.

Los más importantes, sin embargo, son los esfuerzos alrededor de la Educación Bilingüe Intercultural y la ley 88 de 2010. La ley oficialmente reconoce los idiomas y alfabetos de los pueblos originarios de Panamá. Previamente, el gobierno panameño solo reconoció a los idiomas indígenas como dialectos, impidiendo la enseñanza formal de estos idiomas en los colegios. Líderes de comunidades de los diferentes pueblos originarios de Panamá se unieron para impulsar la ley en la Asamblea Nacional.

La Educación Bilingüe Intercultural es considerada por los eruditos Wounaan a ser la mejor manera para preservar el idioma Wounaan para las generaciones futuras. Yoni Cárdenas, experto Wounaan en el Ministerio de Educación, hablo en la Feria Internacional del Libro de Panamá 2023 (que tenía como tema los pueblos originarios) sobre las luchas actuales para impulsar la Educación Bilingüe Intercultural. Describió el proceso de crear un alfabeto Wounaan oficial, trabajando con líderes de distintas comunidades para crear borradores que luego deben ser aprobados por la Asamblea Nacional. Es por esto, dice él, que ha sido tan lenta la implementación de los materiales de enseñanza a los colegios.

Los esfuerzos para preservar el idioma Wounaan son más importantes que nunca hoy en día. Defensores indígenas en Panamá están decididos y esperanzados para prevenir la perdida de sus idiomas.